Despite successfully hosting a most unusual Olympic Games, the spread of COVID-19 still plagues Japan and drags down its economic recovery, even bringing changes in the country's politics. The Yoshihide Suga government, who replaced Shinzo Abe, is now about to leave the office. The problem left to the new Japanese government is not only about effectively dealing with the pandemic, but also pushing for economic recovery in the post-pandemic period. In particular, how Abenomics, which has lasted for nearly 10 years, how it will advance in the future, and whether there will be new changes will also be the main concern of the world vis-à-vis with the new Japanese government.

After Shinzo Abe came to power at the end of 2012, among the series of economic stimulus policies under his Abenomics, the most noteworthy is the loose monetary policy. After nearly a decade of monetary easing and fiscal stimulus policies, Abenomics has indeed achieved greater success, enabling the Japanese economy to gradually emerge from the recession, not only injecting vitality into the financial market, but also beginning to cheer up businesses and consumers. In 2020, under the continuous monetary easing policy, the Nikkei Index has recovered, indicating that the Japanese stock market has recovered from the disasters befall after the 1990s. However, Abenomics still faces the long-term unsolvable problem of sluggish domestic demand, and therefore it is difficult to push up the long-term sluggish inflation level and achieve the 2% policy goal.

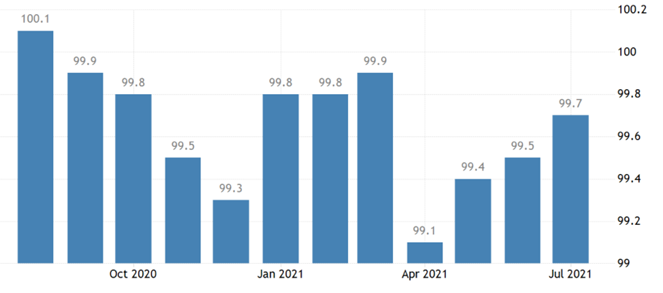

Chart: Changes in Japan’s Monthly Consumer Price Index (CPI)

Source: Tradingeconomics.com

The continuous outbreak of COVID-19 has given the Bank of Japan (BOJ) a new reason for the current deflationary troubles, that the pandemic is the main factor that has made it difficult for Japan’s domestic demand to rise in the past two years. It is also against this backdrop that the BOJ has followed the Federal Reserve and other major central banks to further expand their economic stimulus plans in response to the pandemic. Since the outbreak of COVID-19, Japan has also maintained a loose monetary policy in order to stimulate the recovery of the domestic economy. According to relevant data, so far Japan has invested JPY 34 trillion into the market. Data also shows that after excluding the impact of inflation, Japan’s real GDP growth rate in the second quarter was 0.5% month-on-month, and the actual growth rate year-on-year was 1.9%, which was higher than the country’s previous forecast of 1.3%. From this point of view, Japan's continuous easing plan has achieved certain results. However, compared with rising global inflation, Japan has been struggling with deflation since July last year. By July of this year, the revised CPI index showed that it had fallen for 12 consecutive months, marking the longest consecutive decline since the 28-month deflation in June 2011. Therefore, it is still difficult to explain with the pandemic as the sole reason for this. Under the continuous promotion of monetary easing, whether Abenomics will continue to be effective remains questionable.

As Shinzo Abe's influence on post-Suga new Japanese government will eventually fade, the continued implementation of Abenomics is becoming less attractive to the new Japanese government. After all, the goal of economic growth that Abenomics can achieve has become a reality, and the unachievable inflation target may still be challenging in the future under the framework of Abenomics. It is worth noting that the term of office of Kuroda Haruhiko, the governor of the BOJ who resolutely implements Abenomics, will end in 2023, and his departure is likely to mean the end of Abenomics' monetary policy. His most likely successor Amamiya Masayoshi, the current deputy governor of the BOJ, is expected to adjust the current easing policy in order to restore the central bank's independent role in the implementation of monetary policy.

In tracking Japan’s economic policy, researchers at ANBOUND noted that the BOJ has already begun to adjust from the easing stance of Abenomics. During the spring of 2020, in response to the pandemic, the BOJ has introduced a system of injecting credit funds into private financial institutions at a zero interest rate. According to usage conditions, measures such as giving a 0.1% premium interest rate to the balance of demand deposits held by the BOJ have been taken, and the zero interest rate and negative interest rate policies have been loosened. At the BOJ meeting March this year, the Japanese central bank announced that it will no longer commit to a fixed purchase plan for risky assets, instead will adopt a flexible approach based on market conditions. This is a sign of it to slow down its currency support.

The more significant change in the near term is that the BOJ may further change the negative interest rate policy that it has been insisting on. According to a Reuters report, Amamiya Masayoshi, the deputy governor of the BOJ, who has a decisive influence on Japan’s monetary policy, approved a controversial plan announced in November. According to the plan, the BOJ pays 0.1% interest on deposits held by regional banks that cut costs, boost profits, or conduct business integration. This is a recognition of regional banks’ complaints that the BOJ’s negative interest rate policy is shrinking the already meagre profits, and it also reflects policy makers’ concerns that long-term low interest rates may undermine the stability of the banking industry.

Years of easing policies have caused the BOJ's balance sheet to continue to expand, bringing increasing burdens to its continued promotion of easing. In order to support the capital turnover of enterprises suffered from the pandemic, the capital supply has further expanded. BOJ report shows that as of the end of fiscal year 2020 (end of March), its total assets increased by JPY 109 trillion compared with the end of the previous year, an increase of 18%, reaching JPY 714 trillion, a new high since 2016. This means that the BOJ’s total assets reach approximately 1.3 times Japan’s GDP, which is very prominent among developed countries. In 2018, Japan became the first country in the Group of Seven (G7) that has a central bank balance sheet exceeding the GDP. Among them, the national debt, which accounts for more than 70% of the assets held by the BOJ, increased by 10% to JPY 532 trillion. Loans to commercial banks on the other hand has reached JPY 125 trillion, an increase of approximately 1.3 times year-on-year. The highly controversial ETF holdings reached JPY 35 trillion, making the BOJ the largest market trader in Japan, and it is believed that its huge holdings have caused distortions in the stock market. If the BOJ continues to promote easing policies in the future, it might even become the “largest shareholder” of Japanese companies. With the policy space getting smaller and smaller, the new Japanese government will face a new policy path choice.

Sustained easing of course, cannot resolve the problem of deflation. In fact, it has exposed the long-term structural problems of the Japanese economy, which cannot be improved by stimulating demand. As ANBOUND has previously pointed out, on the one hand, Japan’s increasingly aging population has not only made it difficult to increase consumer demand, it has also exacerbated labor shortages and restricted economic growth. On the other hand, the Japanese government’s monetary policy did not bring about adjustments in industrial policies to promote technological innovation, but merely brought about “false prosperity” in the capital market. Even in the post-pandemic period, the distortion of the global supply chain has brought about a surge in Japanese exports, it is still difficult to reverse the shrinking domestic demand. At present, the BOJ is trying to implement a plan similar to industrial policy to encourage the integration of the banking industry and promote the development of green finance. This may mean that the Japanese central bank will follow the trend of global monetary policy shifts and may try new ideas to normalize monetary policy.

Final analysis conclusion:

The tone of the Bank of Japan's future monetary policy will depend on the new Japanese government, but the motivation and basis for continuing to implement Abenomics in the future have changed. Persisted deflation has narrowed the Japanese central bank’s policy space, forcing it to make new choices.